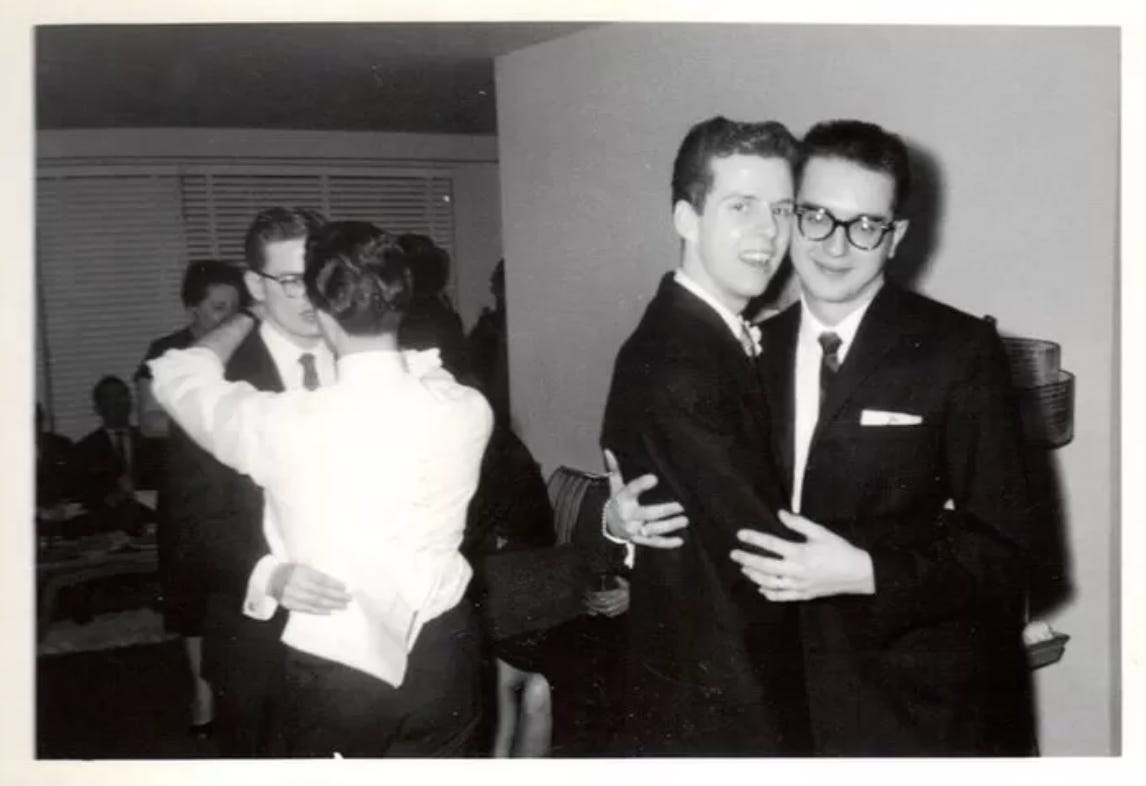

In 1959, 35-year-old Louis A. Barker and 29-year-old Pasquale (Pat) Mattera took rooms together in the Spencer Apartments, a lofty slab of quoin-edged brick along the northern edge of the DeBaliviere Place neighborhood in St. Louis. Black families had been moving into the area since the late 1940s, and of course there was White flight, so rent for the three rooms plus kitchenette would have been manageable for Lou, a salesman at the International Shoe Company, and Pat (nicknamed Patsy), a clerk for the Wabash Railroad. Plus, DeBaliviere Place sat beyond the easy gaze of Patsy’s tightly threaded family, who operated a pizzeria four miles away in the Italian American enclave known as The Hill. The distance gave Patsy and Lou a degree of domestic privacy. For queers in love in 1959, separation from family, if they could afford it, was crucial.

A life-scramblng inheritance following the death of Lou’s grandmother would buy them even greater separation from St. Louis. By 1964, Pat and Lou had moved to California, to a suburb where the houses spread like coastal sage across a steep, wind-brushed flank of the Santa Cruz Mountains ten miles south of San Francisco. They bought a white Thunderbird convertible with red leather seats. They bought a house with few markers on the winding street, just a mailbox, a carport on stilts, and wooden stairs in the hillside, disappearing through a screen of oaks to a front door painted the color of cantaloupe flesh.

On the canyon side, the house was almost entirely a wall of glass, fronted by a narrow meandering deck. The only view onto the intimacy of Lou and Pat’s life was from our house, and the decked and windowed back that faced it across the canyon. My liberal parents embraced them, which made us outliers on the street. I called them Uncle Pat and Uncle Lou. In public, they lived quietly. Uncle Pat went to the office; Uncle Lou stayed home to clean and shop and cook.

At home in their living room looking out past the deck to scrub oaks, the adults drinking cocktails, sometimes with a stack of Broadway cast LPs on the hi-fi’s automatic changer, as I played with Kurt, Pat and Lou’s excitable perfumed schnauzer. They lived buoyant lives, entertaining my parents, sometimes with other male couples who’d driven down from San Francisco for the day; men who cackled over hushed jokes I never understood, even when I caught what they were saying. And yet for all the joy, I could feel the tension in that house across the canyon, stretched so tenuously between poles of private and public.

Once, at a party my parents threw, our neighbor Bob sashayed up and down the deck, wearing a tea towel like a wig and catcalling across the canyon, as other guests snorted and flashed looks at my mom and dad. Another neighbor confronted my mother in a Safeway aisle; asked her if she thought it was wise to expose her son to men like that. And there was that one Halloween, when the word QUEERS was slashed in black capitals on the pink of their door.

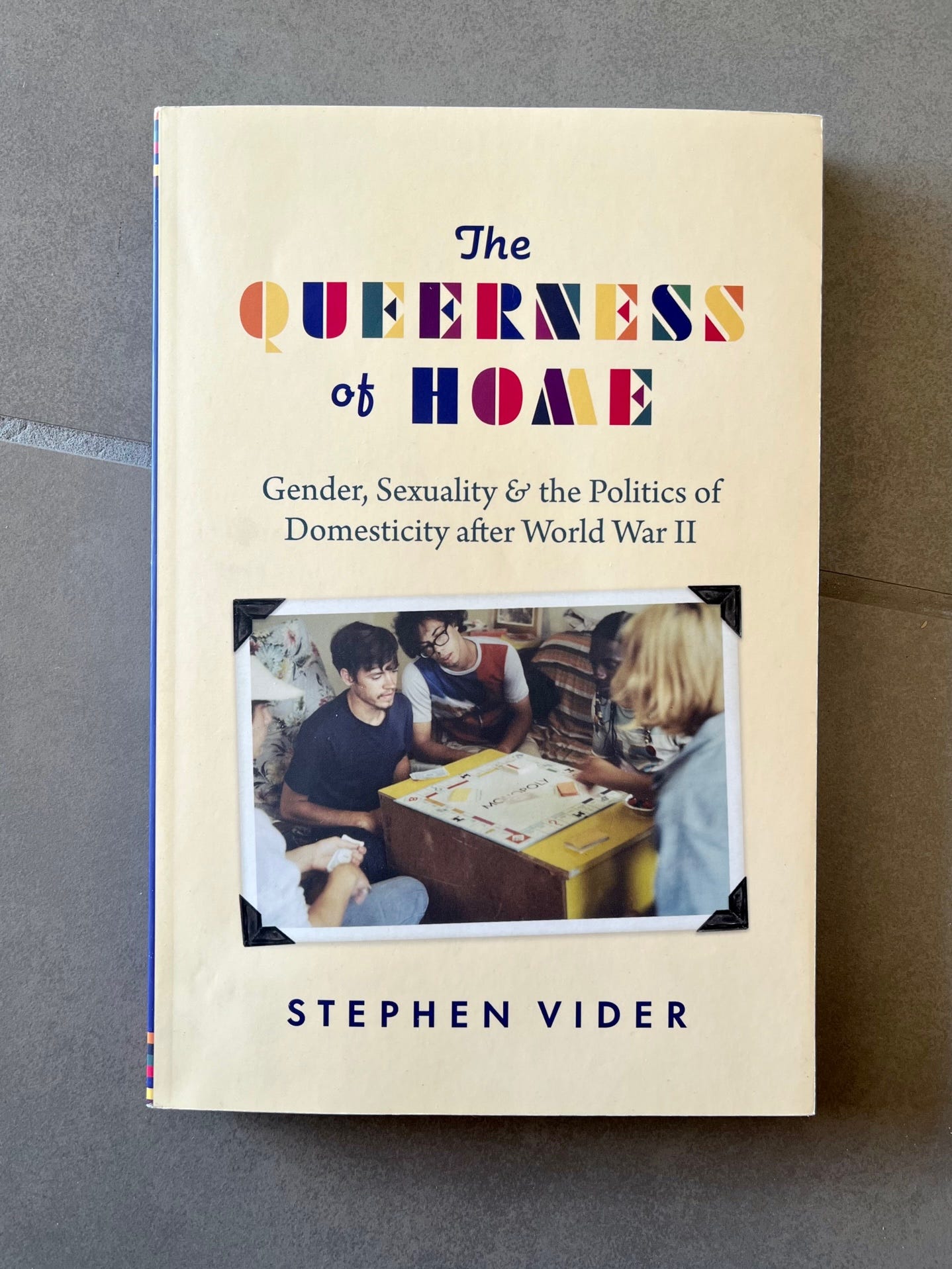

As I grew up—came out of the closet in an era of public queer activism, more than a decade after the Stonewall rebellion of 1969, generally acknowledged as the start of the modern LGBTQ rights movement—I thought of Pat and Lou as part of a tragic gay and lesbian generation, eternally suspended in pre-liberation silence. But after reading Stephen Vider’s The Queerness of Home: Gender, Sexuality and the Politics of Domesticity After World War II, I have a growing awareness of Pat and Lou as revolutionaries, in ways that was possible in a white commuter suburb in the 1960s.

Because then, outside certain small gay clusters, any public visibility at all was a challenge to the enforced monoculture of heterosexism. Anything that looked like marriage between people of the same gender could rate as defiance—Pat and Lou merely walking Kurt round the neighborhood, seeming not to notice the eyes trained on them from kitchen windows; or Lou loading up his cart with sale-priced ground chuck that would keep him and Pat in burgers and spaghetti sauce for weeks, or lunchmeat to make Pat sandwiches for the office. Any queer co-opting of straight domestic rituals could appear an act of vandalism against the heavily riveted architecture of the patriarchal family unit, with its nuclear layout and gender-role buttresses.

Vider, an assistant professor of history at Cornell University, examines four decades of 20th-century queer and trans domestic experience, from the early gay and lesbian civil rights movements of the 1950s to the challenge of coping with HIV/AIDS in the ‘90s. The Queerness of Home is remarkable in being the only LGBTQ history I know of to deal exclusively with domestic life. Earlier books—Gay American History by Jonathan Ned Katz, for instance, or Lillian Faderman’s Odd Girls and Twilight Lovers—toggle between public and private moments, but The Queerness of Home focuses exclusively on the living arrangements of queer and trans Americans and in that, it feels painfully overdue, a welcome revision of an LGBTQ history whose gaze has been locked on Christopher Street and the Castro; on bars, bathhouses, and AIDS wards; on marches on Wall Street and Washington; on messy takeovers of corporate shareholder offices; on courtrooms. Until Vider, no historian has turned their lens onto the comfortably applianced middle-class kitchens of couples like Pat and Lou, the mattress-carpeted apartments of Gay Liberation Front housing collectives in New York City, lesbian-built domestic retreats under geodesic domes of stained glass in Northern California, and the shag-rug communal living spaces in queer runaway youth shelters in Los Angeles.

I’m sure I’m not alone, among readers of queer history, in realizing just how starved I was for Vider’s book until it was in my hands

.

Part of the delay in a historical reckoning of the queer home has been the disagreement within LGBTQ discourse over pursuing same-sex marriage as a civil right. The roots of this debate reach to the early years of queer struggle, and the mid-1950s schism in the Mattachine Society, between a strategy of pursuing equality through radical socialist action, or homophile appeals to a sense of justice from within the prescriptions of patriarchy: black suits for men, flower-print dresses for women, coupling in ways that mimicked straight marriage, except perhaps in private, behind Venetian blinds snapped tightly shut.

The dilemma for lesbian and gay couples of Pat and Lou’s generation, living in de facto marriages—perhaps even advocating, through organizations like Mattachine and its lesbian ally, the Daughters of Bilitis, for legal homosexual unions—was the double-bind of societal validation. Many couples sought public acceptance for domestic arrangements they needed to screen from the sometimes violent intolerance that surrounded them.

Lisa Duggan’s coining of the semi-ironic barb homonormativity expressed marriage advocates’ neoliberal pursuit of heteronormativity, portrayed as the work of cisgender gay men, almost exclusively white, who controlled the donation stream of LGBTQ advocacy groups. Same-sex marriage seemed hung up on middle-class norms of respectability, inimical to the definition bell hooks once articulated for queerness, as “the self at odds with everything around it”; or to Cathy J. Cohen’s famous rendering of queerness as an identity that seeks to change “the basic fabric and hierarchies that allow systems of oppressions to persist,” not one that angles for a seat at the boardroom table, or to take up space on the sidelines of a little league soccer field.

Vider aims to drain same-sex marriage of the privileged characterizations with which critics have flooded it. “Scholars,” Vider writes, “have…tended to use Duggan’s term uncritically and out of historical context, taking the link between domesticity and normativity for granted.” In his critical revision of domesticity, Vider argues that home “has been a crucial though contradictory space in LGBTQ life and politics—a site of constraint and a site of self-expression, a site of isolation and a site of deep connection, a site of secrecy and a site of recognition.” Domesticity is social performance, a stage for demonstrating what Vider calls cultural citizenship, your proof of belonging.

For me, the discussion of marriage is inseparable from injustice, the silence surrounding generations of queer couple in the twentieth century, either because they never told their stories aloud or those stories were erased. For Uncle Pat and Uncle Lou, whose joyful domestic life across the canyon lasted only five years, the state stepped in to reassert its vision of Pat’s cultural citizenship.

When Pat died suddenly of a heart attack at age 39, in 1969, police detectives invaded the house. They questioned Lou, questioned my mother: asked if she knew that Pat and his “roommate” shared a bed. Pat’s family, his stepmother and sisters, arrived from the Midwest to pack his effects up: slide the rings off his fingers, strip the closets of his clothes, and fly his body back to St. Louis, as if California had never existed. As if Pat and Lou’s social performance had been an aberration. It needed to be wiped from the record.

And yet as far back as the early 1960s, queer people were pushing the limits of that performance and leaving records. In 1965, a new publisher based in Los Angeles, Sherbourne Press, brought out The Gay Cookbook by Chef Lou Rand Hogan. The cover copy announces it as “The complete compendium of campy cuisine and menus for men…or what have you,” and presents an illustration of a young man before a barbecue grill—chef’s toque perched on carefully styled locks—in a bow-tied apron printed with the word “Hers”: one hip dropped in a model’s pose, a meat fork cocked like Holly Golightly’s opera-length cigarette holder in one hand, the other limply dangling a bloody steak. The vibe is strongly Paul Lynde, the camp Hollywood actor who, also in 1965, made his debut on the ABC sitcom Bewitched.

Vider delivers a biography of Hogan, the pen name of Louis Randall, who bounced between LA and San Francisco, a frustrated stage performer who worked as a cook and steward on luxury ocean liners traversing the Pacific. The Gay Cookbook, Vider says, “was most innovative in using camp humor to reimagine gay domestic space”—there’s a recipe for “Swish Steak” (i.e., Swiss Steak), and instructions for telling your “butch” (i.e., butcher), how to “grind his meat.” But, except for the sassy line drawings by David Costain, the rest of Hogan/Randall’s book is pretty dull, packed with basic recipes from the europhile American canon, lacking style—the kinds of formulas for duck a l’orange, goulash, and cheese sauce you’d find in any best-selling, phonebook-thick recipe collection of the mid-twentieth century

As a historical document The Gay Cookbook is irresistible, but I wonder if Vider isn’t overstating its influence. “We cannot forget,” pop-culture historian Jessamyn Neuhaus reminds us, “that American citizens did not read cookbooks as a collected group of artifacts from a particular era, the way historians now can.” Did anyone really prop open The Gay Cookbook next to the stove, or was it primarily a gag, a novelty to stash at the back of a kitchen drawer, to be pulled out at a party after the second round of Gibsons along with the naughty cocktail napkins? There’s a much stronger case for the subversive bending of the steel-clad gender norms in midcentury American homes in the books and recipes of James Beard, Craig Claiborne, Michael Field, and Richard Olney, among others, popular gay authors and lifestyle experts working from within the complicated closet of the open secret, who actually did change the way Americans thought about pleasure in the context of food; how they cared for their families and guests.

The invisible thread stitching Vider’s chapters together is the idea of how the understanding of kinship evolved in the US; how queer people effected a change in the wider culture about how we—the broader we, straight, queer, and trans—look at family differently than we did in the 1950s. How the modern conception of family as a chosen tribe is now at least as meaningful as the centering of blood relations. (See the yearly tide of stories in November on how to survive two hours across a turkey carcass with that one fiercely MAGA uncle, bookended with essays about the affirming potluck rapture of Friendsgiving.) Queerness could read as an affiliation of seemingly unrelated people—even straight people—united in resistance to an old, stifling, and urgently irrelevant model of the male-female, breadwinner-homemaker household.

Vider describes how Living With AIDS, a low-budget TV show produced by Gay Men’s Health Crisis (GMHC) from 1987 to 1995 and broadcast on New York public access, showed queer people stretching the image of home. GMHC’s camcorder took viewers through the homes of city residents—most of them queer, many people of color—who were making AIDS care a normal part of daily life, sharing ordinary New York apartments with lovers, relatives, kids. Vider writes, “GMHC’s inreach programs reimagined home not as the private, heterosexual, single-family space that right-wing leaders insisted it was but as a porous constellation of spaces that could link communities and individuals across differences.

Queer people helped rewrite the code for what home means in modern America. They redefined membership in a family, changed what fidelity means, broadened the practice of care, broke old gender rules—even scrambled the idea of fixed, essentialist concepts of gender.

In The Queerness of Home, Vider presents a kind of queer-history course syllabus of home life, a template for future historians—maybe even Vider—to expand on. (His chapter on architect Phyllis Birkby and lesbian feminist architecture, for instance, made me hungry for a full-scale history of post–World War II queer architecture, beginning with a critical exploration of the closeted identity evoked by Philip Johnson’s 1949 Glass House.) Even within its pages, The Queerness of Home left me with an ache for more.

For a book about domesticity, Vider presents little of the quotidian texture of queer lives. He alludes again and again to queer performances of domesticity but omits any telling gestures. What were guests served at Casa Susanna, the private Catskills retreat for trans women in the 1960s? Was the food performative, ruled by the era’s prescriptions? Dainty plates of slenderizing cottage cheese and syrupy canned peaches? Half-grapefruits and black coffee from the all-day percolator in the kitchen? Chicken Divan on Saturday nights? Vider doesn’t say. Should a book about twentieth century queer history be obligated to correct the erasure of queer identities that the dominant culture tried to achieve?

Maybe the highest compliment for Vider’s pioneering history in this book is the emptiness it opened in me, and my desire to stuff that void with every queer quotidian detail in the lives of my ancestors. #

thanks, again. It's a way for me to look at our life and ancestry in ways that don't fall it the trap of abetting the "old, stifling, and urgently irrelevant model of the male-female, breadwinner-homemaker household"

Couples like your uncles were always less tragic and more heroic in my measure; it's good to see them read that way (and to hear more about these beloveds of yours, period).

I so appreciated Faderman's book when it came out, but reading your piece I'm thinking now about the binaries we (all of us, queer or not) impose. (Thank the ancient Greeks for that.) In the SF of the early nineties in lesbian (couldn't be bi or pan and out there very well) culture, the firm rejection of birkenstocked, unsexualized, mirror-image partners in favor of a strong butch/femme aesthetic, with the femme publicly in charge, was a reclaiming not of domesticity but of sexuality and feminine power. And: a binary choice.

Also wondering whether diaries and letters reveal a bit of that lost queerness-at-home. Rebecca Cox Jackson's "autobiography", the letters of Violet Trefusis and Vita Sackville-West, the ponderous journals of Anne Lister...come to mind.

Thank you for the food for thought.