Richard Sax and the Silence of AIDS

The pandemic the food world has never fully acknowledged.

Hello! I’m dismantling my existing website and moving its contents to this newsletter. I wrote this essay a couple of years ago, and have just now revised it. In the weeks to come I’ll be unpacking more of my pieces, and updating them. As always, thanks for supporting writers who don’t always fit within the shrinking dimensions of commercial boxes!

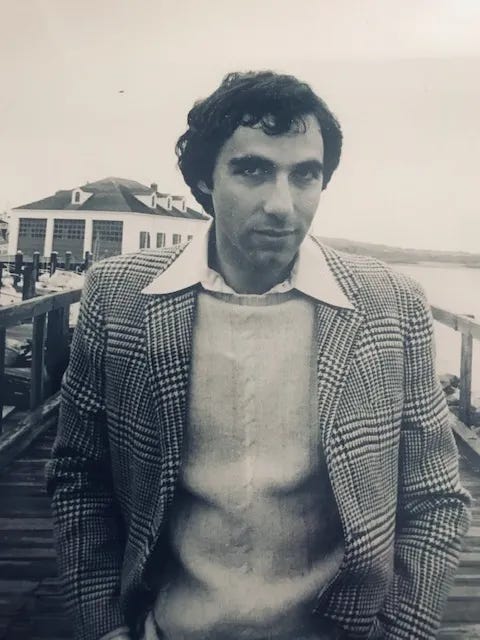

By 1979, 30-year-old Richard Sax had pulled off the kind of reinvention that was possible for young lesbians and gay men who arrived in New York in the decade after Stonewall, when Greenwich Village shook, old walls toppled, and ambition started to wrap itself in the colors of identity. Pastry chef Nick Malgieri met Richard that year. He was dark and lanky, with soft eyes and a chin dimple set just off plumb from the centerline of his lips. Malgieri noted how meticulously Richard had assembled himself: his jeans, flannel shirt, and cowboy boots, a look as tight as flexed muscle.

That same year, Food & Wine founders Ariane and Michael Batterberry hired Richard to carve a test kitchen out of their rambling editorial offices, filled with the Batterberrys’ collection of antiques and odd knickknacks, on Third Avenue at East 47th. Richard and the Batterberrys were building the architecture of the modern glossy food mag.

Three years earlier, Richard was a high school English teacher in Clark, New Jersey. Even there he’d begun a personal transformation, sort of Venice Beach coffee-house poet, wind-zhuzhed surfer hair and Earth shoes. He had ambitions to be a great cook. On weekends he catered, mostly hors d’oeuvre parties, prepping in his apartment kitchen in Orange.

In the summer of 1977, he took a job running the Black Dog Tavern on Martha’s Vineyard, a place of creaky, raw-board floors and clenched New England restraint. Richard saw the romantic possibilities: white tablecloths and votive candles. Fishermen wheeled pre-dawn hauls to the back door; there was local corn and tomatoes, and watercress that some enterprising hippies foraged in the creeks.

The next year Richard went to Paris to study at Le Cordon Bleu, followed by a kitchen apprenticeship at the Hotel Plaza-Athénee. In London, he went to work for Richard Olney on the Time-Life Good Cook series, the multi-volume subscription cookbooks memorable for step-by-step technique photography. Unfortunately for Richard, Olney gave him responsibility for the volume on offal, a subject that made Richard queasy. At first he refused to style the split and baked lambs’ heads, but Olney insisted, made Richard peel the lips back and brush the teeth so they’d shine for the camera. Eventually, Olney, who was often absent, accused Richard of moonlighting, sneaking into the studio kitchen to test recipes for a book of his own. Olney fired him.

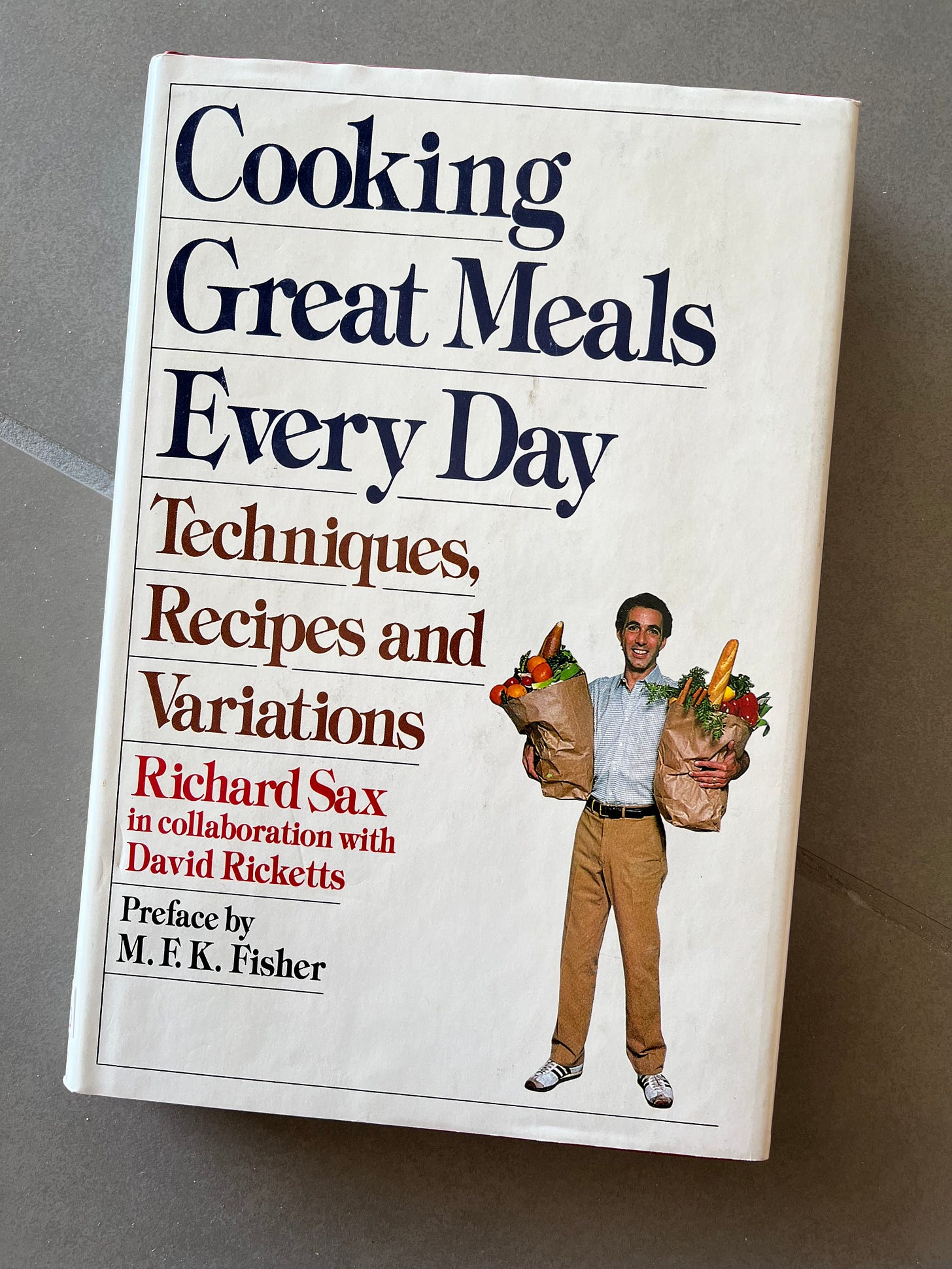

Back in New York, Richard worked for Food & Wine while writing a string of books: Cooking Great Meals Every Day, in 1982, with David Ricketts; The Cookie Lover’s Cookbook in 1986, same year as From the Farmers’ Market, with Sandra Gluck. It was during this period that Richard fell in love. Michael Violanti was gorgeous and funny, with curly dark hair and intense eyes. A first-gen tech geek from Detroit, he launched a telemarketing company in New York.

Michael and Richard moved into a big loft in Soho, a minimalist space in black and gray on the eighth floor, with a bank of windows looking onto Broadway. Richard hosted cooking classes there. On summer weekends, they escaped to Fire Island, eventually buying a place of their own in the Pines. Gluck and her husband would go out to stay, partying in the gay crush of Michael and Richard’s friends, in a haze of tea dance DJ sets, blue margaritas, poppers, weed. The house had a small lookout at the top of a ladder, an antique avian garret known as a cockloft, though of course it was extra-delicious because, well: cock.

There were 6,871 new AIDS cases reported in New York City in 1989. Nationally, deaths from AIDS-related illness spiked to over 19,000. Nick Malgieri remembers getting together with Richard, in that terrible year of soaring numbers, at a restaurant in the West Village. It was late afternoon and Richard seemed preoccupied. After a while, when the restaurant was nearly empty, Richard told Malgieri that Michael was starting to show symptoms. “That was the start of our friendship,” Malgieri says, because in those days—when the fear and stigma of AIDS haunted a city already ravaged by the pandemic—you didn’t talk about infection with anyone you didn’t trust.

Michael died in 1991. A devastated Richard sold the loft and bought an apartment uptown. His friends noticed changes in Richard beyond the grieving. “I knew the writing was on the wall,” says Marie Simmons, his coauthor for a monthly recipe column in Bon Appétit magazine. Malgieri was at Richard’s apartment for a meeting of the culinary group Bakers Dozen East. Malgieri got there first, and on Richard’s kitchen counter noticed a ramekin of pills: AZT (azidothymidine), an antiviral that can delay the onset of symptoms, a sign that Richard had been diagnosed with HIV. The side effects could be brutal. “Nobody took AZT for fun,” Malgieri says.

Meanwhile, Richard had begun work on cookbook he hoped would be his legacy: a sprawling compendium of American home desserts. It was to be a synthesis of historical and modern recipes; he spent long hours in the New York Public Library’s vaultlike rare book room, poring over recipe notebooks and early cookbooks. For inspiration and recipes, he asked friends and colleagues, a Rolodex of pastry chefs and recipe developers that included Malgieri and David Lebovitz. He collected quotes from literature to grace the margins of the pages. Richard’s research was meticulous, and his pace was frenetic.

The virus had its own schedule. Richard developed Kaposi’s sarcoma, a form of cancer that can cause purple lesions in the skin and organs. He labored to breathe after the lesions got to his lungs. He did chemo. His weight dropped. His hair fell out.

He was asked to present an award onstage at the IACP convention of 1994. He had the courage to stand at the lectern and show himself to a hall full of colleagues—a 45-year-old man whose body was no longer on a predictable arc, but was fixed instead to the virus’s laws of time. “He was wearing old-fashioned rimless glasses,” Malgieri says. “He looked like Richard Sax, 80 years old.” As if the truth that others were not supposed to hear had found its own way of speaking.

Queen of Southern cooking Nathalie Dupree saw Richard that night at IACP. Her advice to him echoed the sadness and alarm of many who knew him. “Now, Richard,” Malgieri recalls Dupree saying. “You go home and make a pan of brownies and eat every one!”

Richard’s grand book, Classic Home Desserts, was published in 1994. He dedicated it to Michael, his “beloved friend,” a kind of muted public coming out.

At the 1995 James Beard Awards ceremony at Manhattan’s Marriott Marquis, New York City First Lady Donna Hanover Giuliani and Lifestyles of the Rich and Famous host Robin Leach presented Richard with a medal. Four months later, Richard was gone. Before he died, he planned and paid for his memorial lunch at The Four Seasons, where waiters poured rare wines he’d collected but didn’t live to taste—the final gesture, perhaps, in Richard’s twenty-year act of self-invention.

His obituary in the New York Times cited lung cancer as the cause of death. Out of respect for Richard’s mother in New Jersey, who would have been embarrassed by a public acknowledgment, there was no mention of his coping with HIV/AIDS, his cancer’s catalyst. Despite growing visibility of the disease—and belated action from Washington—fear and stigma had largely quarantined the subject of AIDS, except in queer and activist communities. America’s restaurant industry and food media, devastated by the disease, were no different.

There were exceptions. In the Bay Area, Alice Waters and Vince Calcagno organized Aid and Comfort, a pair of fundraisers in 1986 and ‘87 that acknowledged the devastating losses to Northern California restaurants. And Peter Kump, founder of the James Beard Foundation, wrote frankly in the organization’s newsletter about the death of his partner Doug Campbell. But mostly, mainstream food stayed silent as chefs like Michael James, a protégé of Simone Beck who founded a celebrated Napa cooking school; or Sophronus Mundy, opening chef of the Empire Diner in Chelsea; or Billy West, founder of Zuni Café in San Francisco; or Felipe Rojas-Lombardi, the Peruvian-born chef said to have brought tapas to Manhattan. They gave up the complicated, shifting bargains they’d made with the disease to cope with living. They were remembered in coded obituaries that avoided direct mention of AIDS: the ultimate silence in lives in which not speaking was a strategy learned early.

Richard, however, left a sort of memorial of his own, on page 644 of Classic Home Desserts. Next to the recipe for Slushy Melon Ice with Cointreau is a quote from Armistead Maupin’s Sure of You from 1989, the sixth in Tales of the City series, novels that mostly follow queer and trans characters in San Francisco.

In Richard’s quote, Thack Sweeney, fearing his boyfriend Michael “Mouse” Tolliver will soon die from complications linked to AIDS, ponders eating ice cream with a buddy.

With ice cream bowls in hand, the guy asks Thack if he’s frightened.

“Thack shrugged. ‘All we’ve got is now, I guess. But that’s all anybody gets. If we wasted that time being scared . . .’” There’s a pause. They focus on the scoops before them. You imagine the sounds of spoons clinking against bowls, scraping the sides, but otherwise there’s silence.

Richard Sax left us with a manual for pushing fear aside, a book of sweets that offers the opposite of escape, where pleasure is a channel of consciousness, a way of being deliberately human. “Good food is one of the most immediate forms of pleasure available to us,” Richard says in Cooking Great Meals Every Day. “No less than sex or art, food offers total involvement in the realms of appetite, sensual pleasure, and the imagination.”

Food can root us in a body, if we stay open to it, in lives gauged not in tallies of years but in impressions; in feeling. That is all anybody gets. The tragedy is that, by ignoring AIDS and its lessons, the newspapers and magazines we looked to could have made us better humans by breaking silence; by letting us feel the sad and beautiful edges. #

This made me weep. In 87/88, I was at Dean & Deluca when it was at 121 Prince; Agnes B was across the street and next to it, Sax’s little soup/sandwich shop. We, the employees of D&D were made to move the store to 560 Broadway; I remember carrying a copper turbot poacher from Villedieu the few blocks east to the new location (the owners refused to hire movers, and by them I do not mean Giorgio), and I remember hearing talk of Sax’s place closing. By then I don’t even know for sure if it was his place. I left the store a year or so later, and learned about five years after that, that every single man I worked with was gone, except for the owners and Jim Mellgren, who was my (wonderful) boss. This is a heartbreaking piece, and Olney sounds like, well, Olney. Thank you for writing it 🙏🏻❤️

There is so much (info and great writing) in this piece that I had to read it twice.

Being an oblivious West Coaster, I didn't know of Richard Sax. I was, however, heartened to know that Ms. Gluck is part of the story. My ex and I used to stay at Sandi and Ralph's whenever we visited New York. I thought them marvelous humans.