Enjoy this free post from SHIFTING THE FOOD NARRATIVE. Please consider becoming a paying subscriber.

“The reason I love cookbooks,” Laurie Colwin writes in More Home Cooking, “is that cookbooks leave out all the other stuff. You don’t have to find out about family relationships… It’s just the food.”

No.

No, because “the other stuff” is always only invisible in cookbooks if you will yourself blind. Maybe also numb, since a cookbook can burn and be the salve. Can remind you of the family you had to sever, or be the last remaining artery you couldn’t bear to cut. Every recipe is a gesture in a stretched narrative. “Once I got almost the whole way through a really lovely detailed novel about cake,” @anicegreenleaf says on Twitter, “before I realised it was actually a cookbook by Nigella Lawson.”

Every recipe is a plea for change cast as moves that bind reader to author, novice to guide. Every recipe imagines an epiphany from a set of commands, words that animate our hands, the muscles in our forearms; words that direct our tongues to experience taste in an act of shared intimacy. “The imperative mood can be so intimate in its rudeness,” Tejal Rao writes, “like a mother or a friend speaking plainly: Skin the chicken. Tell me everything. Crush the garlic.”

Every recipe is a plea to change a world cast as deficient, a place of unfulfilled potential, maybe bad, maybe broken. A collection of recipes is never “just” the food.

I spent the 1980s as a cook first hungry for change, then desperate for it. Cookbooks delivered the only imperatives I could trust.

I came out in San Francisco in the summer of 1981 when, at the periphery of apprehension, an unnamed killer ruffled the pages of the queer weeklies, the free papers stacked up next to cigaret machines in gay bars. A year later, not long before I left my soul-parching job as writer for a trade magazine to become an apprentice restaurant cook, the CDC gave this killer a name: Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndrome. Back then I was too afraid to go out. Back then I didn’t really trust anyone besides Elizabeth David

Beginning in 1948, when she sat down to write, David raged against the wiping of joy from British life. Beneath the text of short, impressionistic recipes named “Soupe Catalane,” or “Suliman’s Pilaff,” David drove an argument that drab food represented a muffling of desire.

From my growing stack of used paperback reprints from the early 1970s of David’s iconic first titles, A Book of Mediterranean Food and French Country Cooking, I absorbed lessons in the power of sex; how to cook on the perpetual edge of imagination; sustain the urgency of wanting. How food could so recklessly assert a pleasure unmeasurable in eighth-teaspoons and precisely packed cups—recipes rejecting the sort of replicability that Julia Child would so assiduously pursue. How a cuisine of spices, garlic, and ripe, jammy figs mapped a new geography of the ecstatic imagination—the ingredients scarce in a post-war Britain that seemed content with the sticky horror of mixes, sausages stretched with protein powder, gravy stirred up from flour and cabbage water.

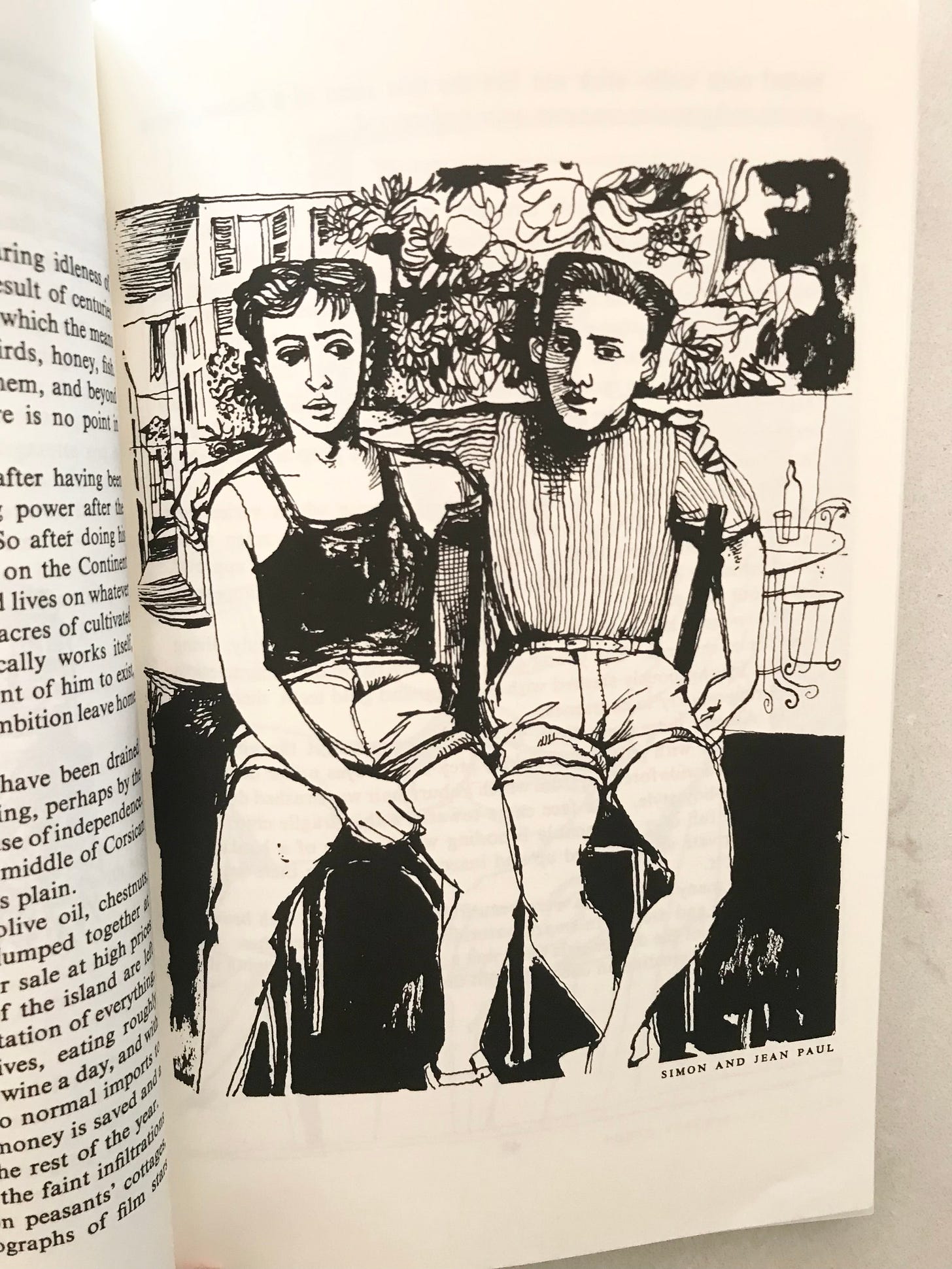

A publisher and poet living the gay open secret, John Lehmann, brought them out, after bigger houses rejected David’s first manuscript. And illustrated by John Minton, also gay, with scenes of Mediterranean street life framed by wandering-eyed market boys and sailors who seemed to have learned loitering from Genet’s Querelle of Brest.

The frontispiece to French Country Cooking: A boy and girl toasting each other with a glass of wine, some grand Loire chateau in the distance. In the foreground a savage cross-cut of a ham with a knife’s blade flaunted: the look of wariness in the girls eyes, trained on the boy who looks ready to devour: his thick jaw, sleeve rolled to expose muscle, in such contrast to his small, delicate sabots. Abundance, a tropical florescence almost sickening: the tureen of soup that demands our looking. Meanwhile through a set of receding portals and a doorway, across a courtyard, there is a small grand arch against which a faceless man leans, near a woman who is either approaching or retreating. The soup is a trap—set by the woman, perhaps—a tease, a lure into this ambivalent dream landscape with its savage weight of ink also marking the wine.

Or another Minton in French Country Cooking: a street receding, ascending into hills dotted with trees: a scrub-country backdrop just beyond a suggestively squalid village street, the semi open shutters of a hotel, and a market vegetable stand, under a canopy shielding obviously fierce heat, under which a shoeless boy in a tight striped teeshirt reclines among fleshy lobed and twisted cucurbitae. He’s crossed his arms in a relaxed way, hands crossed over where his abs would be exposed. He’s looking at a girl walking past with a basket of those squashes on her head, her gaze turned to him, seductive and perhaps regretful that she can merely look, since another woman, wearing a sun hat and bearing a platter of what might be potatoes, could be lemon cucumbers, flanks the stall, keeping an eye on the girl’s flirtatious passage.

I knew this transgressive scene, know the claim the lady in the hat seems to have on this boy. The reason I love cookbooks is that I have felt the ache of that particular thirst.

Please consider becoming a paying subscriber to SHIFTING THE FOOD NARRATIVE.

Your writing is simply sublime. I always earn and enjoy in equal measures. x