Please consider becoming a paid subscriber to Shifting the Food Narrative, for full access to future essays, interviews, and the odd recipe. Thank you.

Read Part One.

It was thirty-five years ago when I invited my older brother and his wife to dinner at the flat I shared with my boyfriend in San Francisco. They were right-wingers who didn’t like gay people (they’re still that), but we always made what I thought were honest efforts to avoid describing the texture of our lives: his church groups and Marriage Encounter sessions, my…everything.

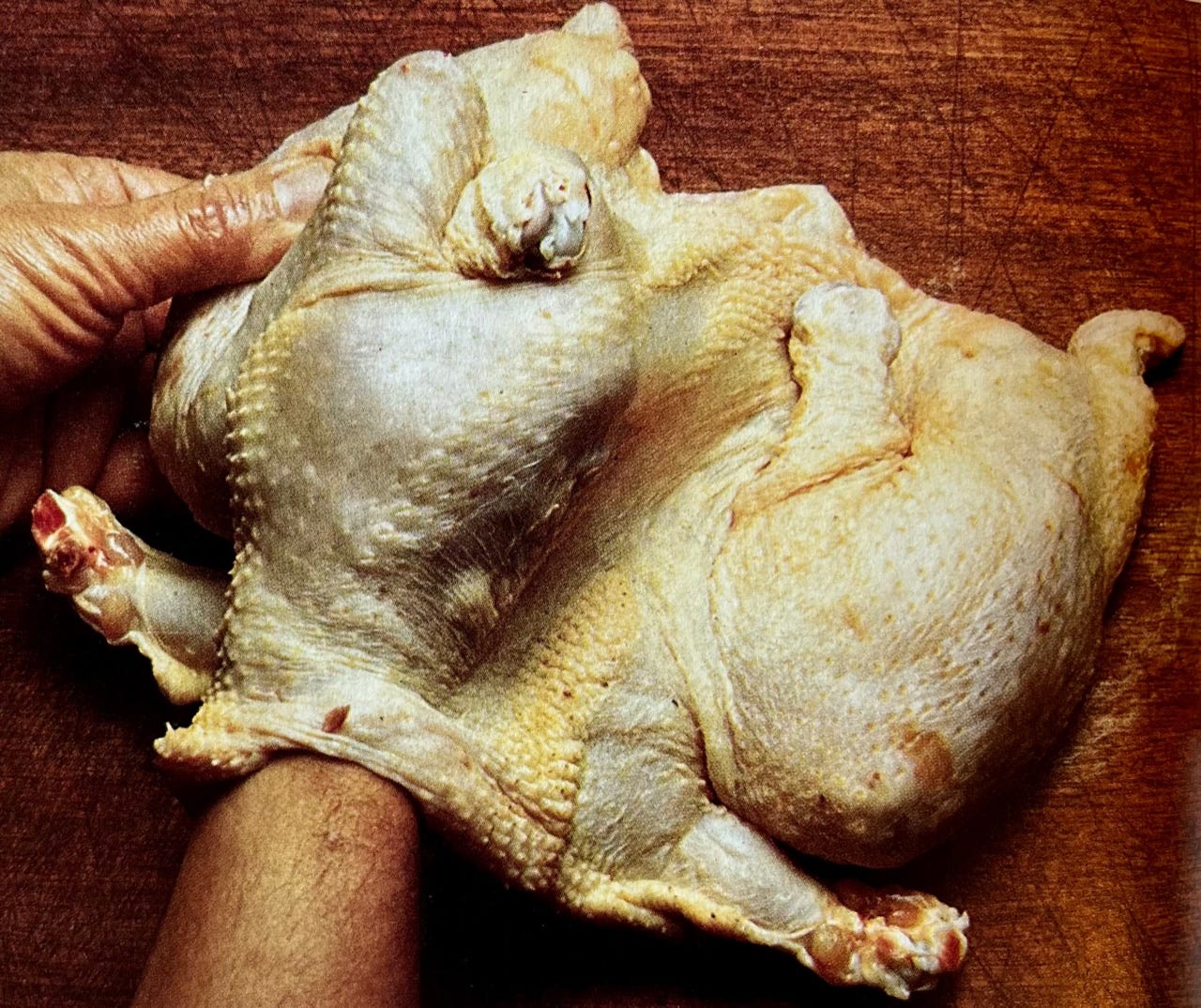

That night, I roasted a chicken I’d stuffed under the skin that turned out puffed, brown, and blistered: took fromage blanc and mixed it with lots of herbs, lemon zest, and the bird’s liver, pounded to a paste with garlic. There was scant conversation during the meal—well, that wasn’t surprising. Later I found out from my mom that my sister-in-law was furious about what she saw as my sabotage: back when I’d invited them, I asked if there was anything they didn’t eat and I recall her mentioning “offal.” And yeah, I guess a chicken’s liver qualifies as organ meat, but to my mind the whole thing, over some tiny, slippery, blood-brown piece of liver, pounded unrecognizable and spread across the surface area of a three-pound chicken, was ridiculously overblown. My sister-in-law only knew it was there because I’d mentioned it.

That was my first encounter, way back in the Reagan years, with conservative grievance. To my sister-in-law, I was an insufferable gay food snob who’d made a trip across the bay to Kermit for wine; who’d slipped an organ into her food to humiliate her lack of sophistication. Me and my people demanded special rights for lesbians and gays; we’d tainted the nation’s blood supply with AIDS through our reckless, dehumanizing hedonism. We were callous and selfish. We were godless. We were evil.

It was clear I needed to cut myself off from all but the barest life-support relations with much of my blood family, outside of my consistently supportive parents. That I had to free myself from the pull of nostalgia for a shared food life with my blood family, of sharing a table with my brother. I was done. In the first part of this essay, I asked what queer people were to do with pasts that are hostile to us—blood families that rejected us; that dishonor the adult families we’ve gathered around us. What are we to do with nostalgia for foods from our corrosive pasts? The idealized food norms of families that rejected us for being queer. In exile, many of us mourn the families we’ve lost, and try to recreate the dishes and food celebrations of personal histories we know to be toxic but can’t give up.

In The Future of Nostalgia, the late Svetlana Boyim distinguished between two types of nostalgia: restorative and reflective. How “restorative nostalgia,” as she called it, “stresses nóstos (home) and attempts a transhistorical reconstruction of the lost home. Reflective nostalgia thrives in álgos, the longing itself, and delays the homecoming—wistfully, ironically, desperately.”

Is there a way of reinterpreting the foods of the our past on our own terms, in resistance to the toxic norms they represent? Can we reject, in Boyim’s terms, the restorative nostalgia that the past can demand of us, and instead re-create the dishes and food life of our past in gestures of reflective nostalgia, wistful for the traditions they connect us while staying true to who we are, as evolved adults, in control of our lives?

Reflective nostalgia is the scar we bear as a mark of pride, the memory of endured trauma that keeps us in mind of our humanity, our frailty, our need for one another. Reflective nostalgia keeps our vulnerability fresh: Nostalgia is an act of creative remembering, mythologizing food of the past as a way to make trauma bearable, to bend it toward transcendence.

Badia Ahad-Legardy, in Afro-Nostalgia: Feeling Good in Contemporary Black Culture, shows how nostalgia can become “more than a benign or regressive category of memory but rather a cultural practice that reframes, and at times repairs, traumatic historical memories.”

Nostalgia can kill and nostalgia can give meaning and purpose—by separating the desire to return to the past from the way a past can help us to a complex, life-giving identity. It can define us in healthy ways, not chain us to controlling identities. I inherited a longing for food I could never actually taste. It was a way for my family to try to build a bridge to me, to give us a connection, a shared urgency that might substitute for love.

There was a kind of hopelessness in the gift: the adults I cared about handed me this longing I think with the hope that I could fill it for them.

In many ways my eventually becoming a cook, though my parents were disappointed I didn’t pick a career with fewer burns and better pay, was to honor their yearning for food that held power and meaning; that could help make sense of the world.

Can I dedicate my nostalgia to some collective expression of solidarity? Squeeze it to yield a sense of kinship not bound to blood? Is there a nostalgia that builds and affirms, rather than reducing possibility? A nostalgia that is actually restorative, revealing who we are in the purest sense, untethered to family live or dead? Is there a queer collective memory of food to be discovered? A cultural practice, to borrow from Ahad-Legardy, that could reframe and even repair queer trauma: the excavated organ, become a delicate remembrance of blood we’ve learned to carry just beneath our skins. •